All societies and businesses across the world are similar in one area – that they all face the same economic problem, trying to maximise the utility of limited, scarce resources.

A simple example of that in the industry is the hospitality, or accommodation, field. How can management ensure that these resources are best allocated for maximum profit with limited rooms, villas, or otherwise accommodations available?

Another clear case of this is a business that needs to accommodate its personnel due to travel requirements, for example, in the resources sector. They may have to decide how to best allocate their similarly limited accommodation resources to ensure all required personnel can be where they are required. If this is not performed adequately, there may be expensive consequences – spending large amounts of capital on building more infrastructure for accommodation or extending scopes of work that could be completed in one to multiple sets of flights, potentially increasing the downtime of the resource.

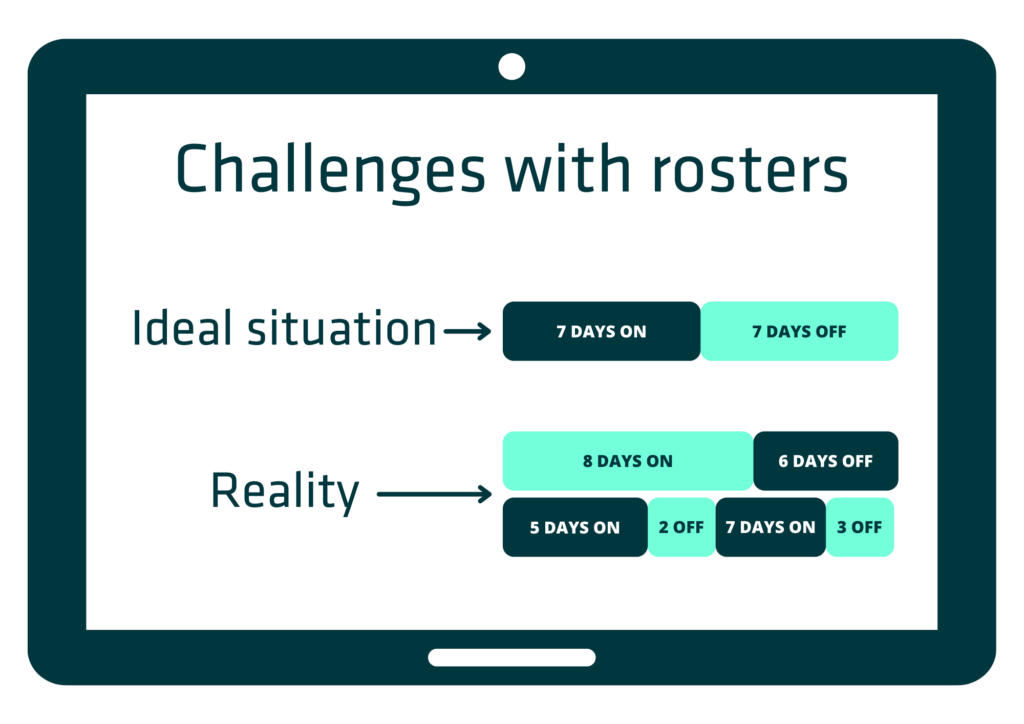

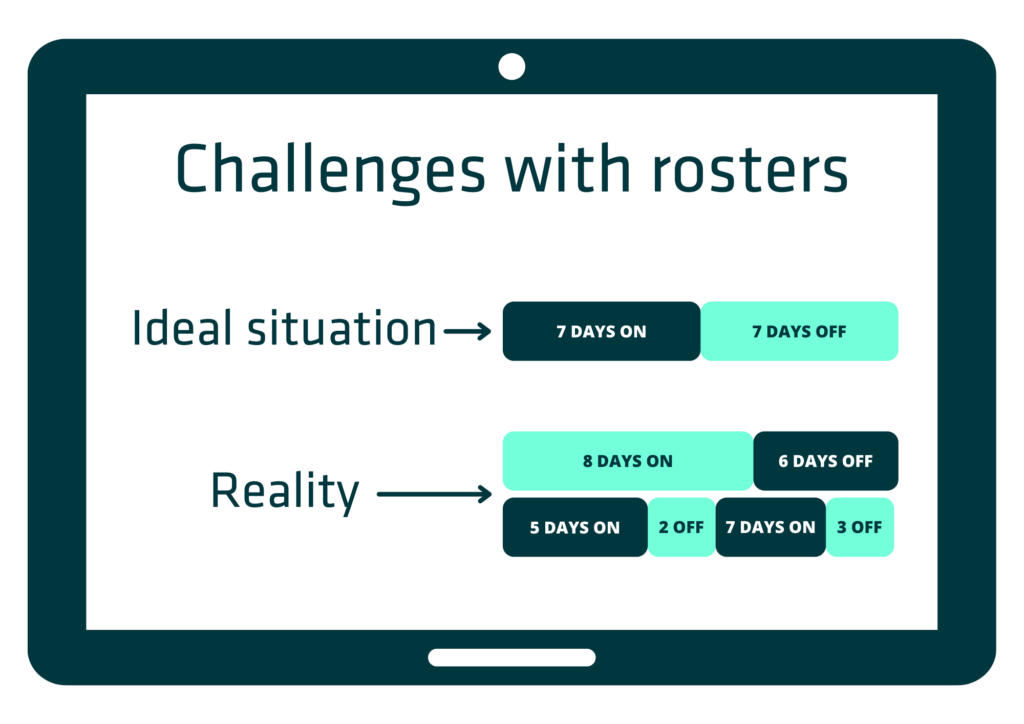

Take the example of an oil and gas company – they need personnel on-site to run the rig, perform maintenance, supervise, and conduct daily routines 7 days a week, 24 hours a day. However, there are a limited number of rooms available at the rig to accommodate this personnel, each of whom may be operating on a different roster and require varying periods at the rig. The problem becomes significantly more complicated than if everyone was there on a 7/7 (7 days on, 7 days off) roster, for example, with two groups alternating. In reality, there are likely innumerable different types of rosters, with erratic days of commencement of the week, due to varying requirements.

We can treat this situation as an optimisation problem – the company is constrained by available accommodation (i.e. the number of rooms). The objective is to maximise utilisation of the available capacity, consequently maximising production efficiency. The clearest available variables to be adjusted include the number of employees on each roster and the schedule of each roster (effectively the number of nights each employee will require the accommodation for). Naturally, more complex variables can be changed too, but with complicated consequences – for example, the amount of capacity available or the number of employees required on-site. However, these would cause significant effects on expenses and potential profitability.

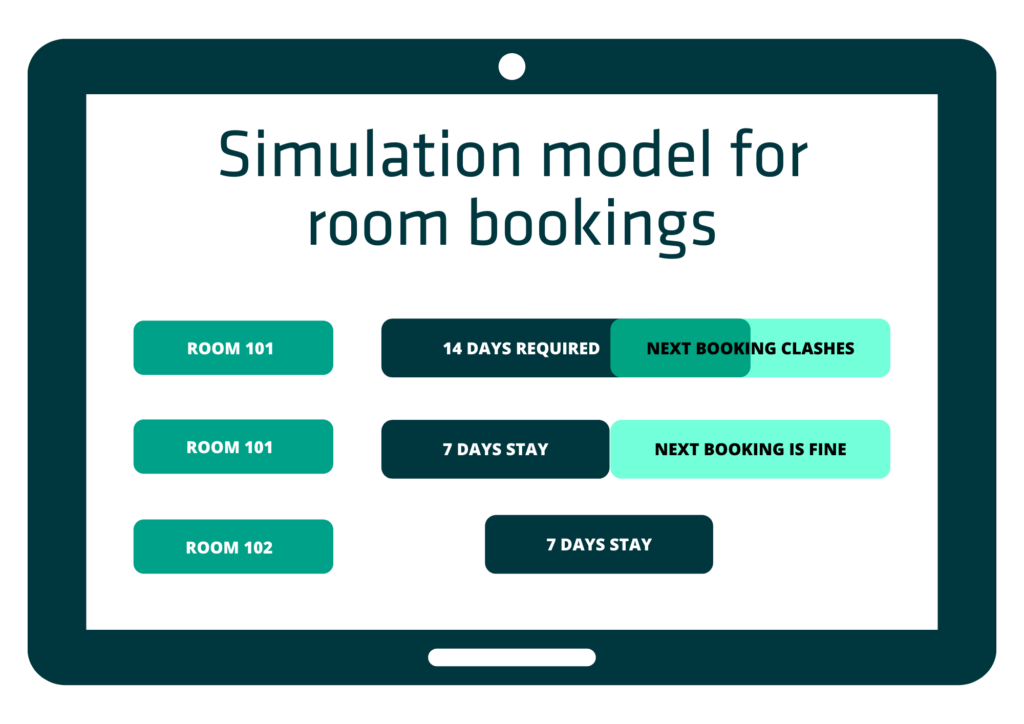

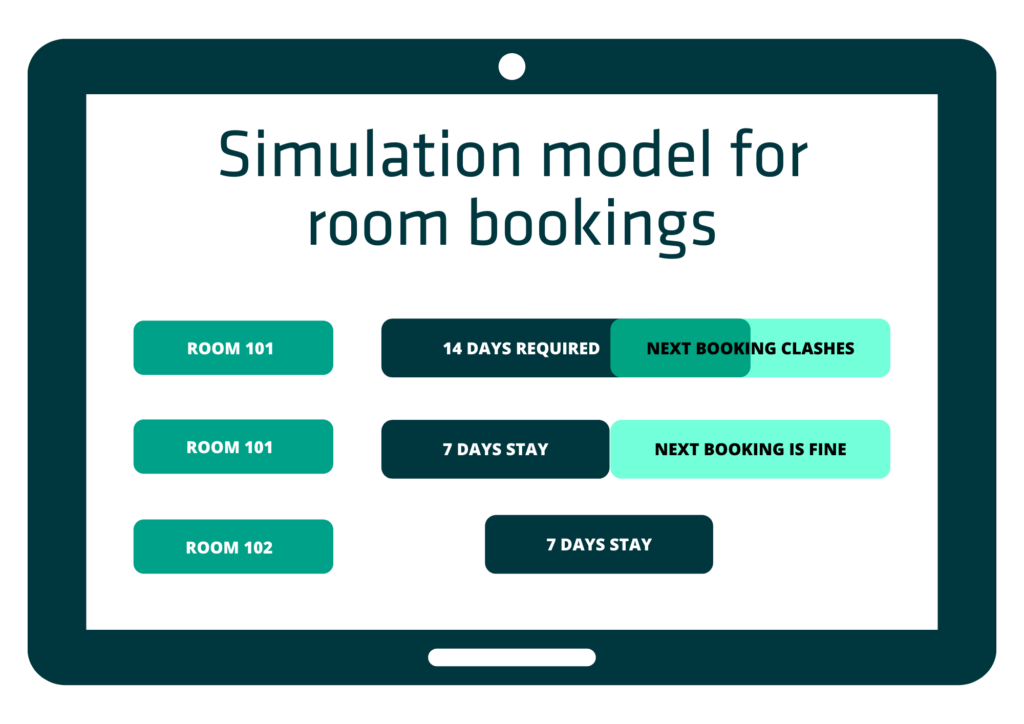

Most market solutions for this currently consider if rooms were only offered to personnel when they are available for the entire period required. For example, if an individual is going to a site to work for the next 2 weeks, a room has to be empty for the next 14 days to be booked for him – if it is occupied on day 1 but available on days 2-14, it would not be suitable. This logistical method is not a problem if there is an abundance of rooms available. However, this is often not the case. To minimise costs, most work sites would often be designed in a way they can become a constrain quickly. Similarly, many hotels in the hospitality industry can face capacity constraints during peak periods.

This leads to a high wastage of rooms that may be available for one or two nights – insufficient for a full rotation at a site or for a usual-length vacation in a resort hotel. How can the business push for these extra nights to be utilised as well?

We suggest an approach that utilises a simulation model, which allows for more flexibility in arranging bookings and with a clear capability to increase the utilisation of available resources. The main concept behind this is allowing for split bookings – a 14-night booking can be considered two separate 7-night bookings, for example, allowing a site that has no rooms available for 14 nights consecutively to still accommodate this individual by having him swap rooms once during the stay.

By optimising the limited resources (rooms) with the high demand of requirements (individuals) and allowing for interruptions along with the stay, gaps can be pieced together to form meaningful stay periods that can accommodate more requirements.

Similarly, guests who wish to make a 7-night booking at a hotel may be outright rejected for the hospitality sector despite 3 nights available at room A and 4 subsequent nights open in room B. If this were presented as an option to the guest, and they chose to accept, the hotel would unlock additional revenue that was previously unavailable. The hotel may decide to present a credit, or another form of compensation, for the inconvenience to this guest. It may not even be required as the guest may be grateful to be offered accommodation where it would generally be unavailable.

In performing this split-booking logistical operation, the cost must also be considered. While increasing functional capacity and potentially increasing available personnel on-site (for the O&G case) or increasing revenue (for the hospitality case), there is a precise cost to this method of operation – convenience. The inconvenience generated from an individual having to move rooms mid-way through their stay is significant but can be alleviated somewhat.

In the hospitality case, we have previously addressed this by offering compensation to any guest inconvenienced and offering it as an option rather than a forced choice. In the O&G case, a few considerations are important.

Firstly, there should be a minimum consecutive-night condition, where no individual will be made to shift rooms when having stayed less than a certain number of nights. This lower bound can be determined by surveys to the main stakeholders who will be affected, combined with discussions among management regarding additional costs and employee satisfaction.

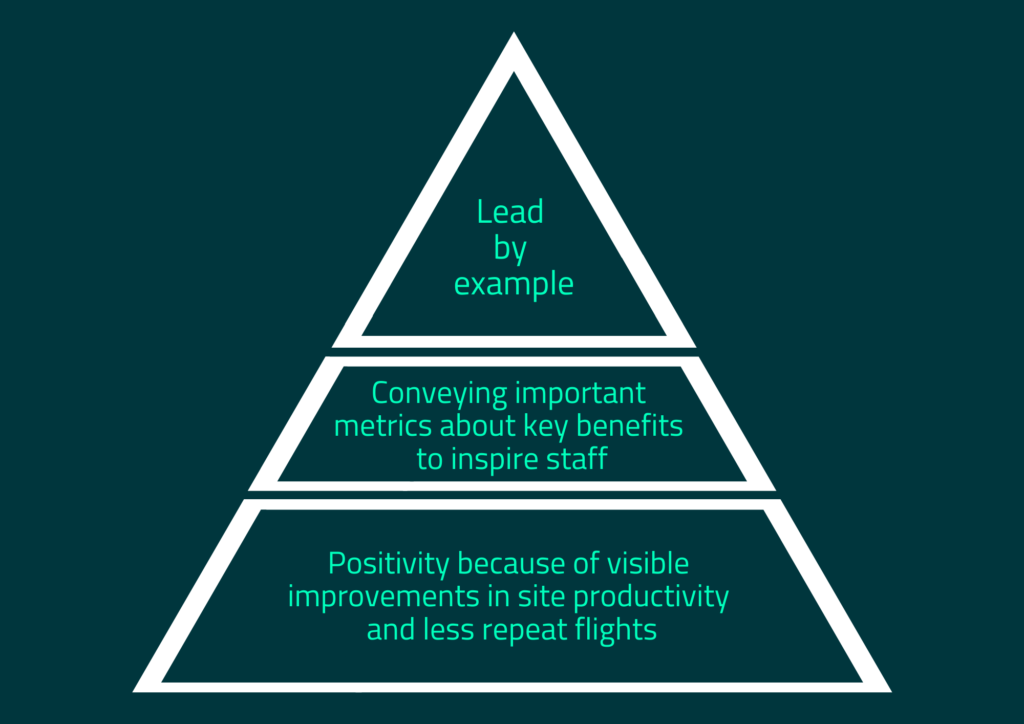

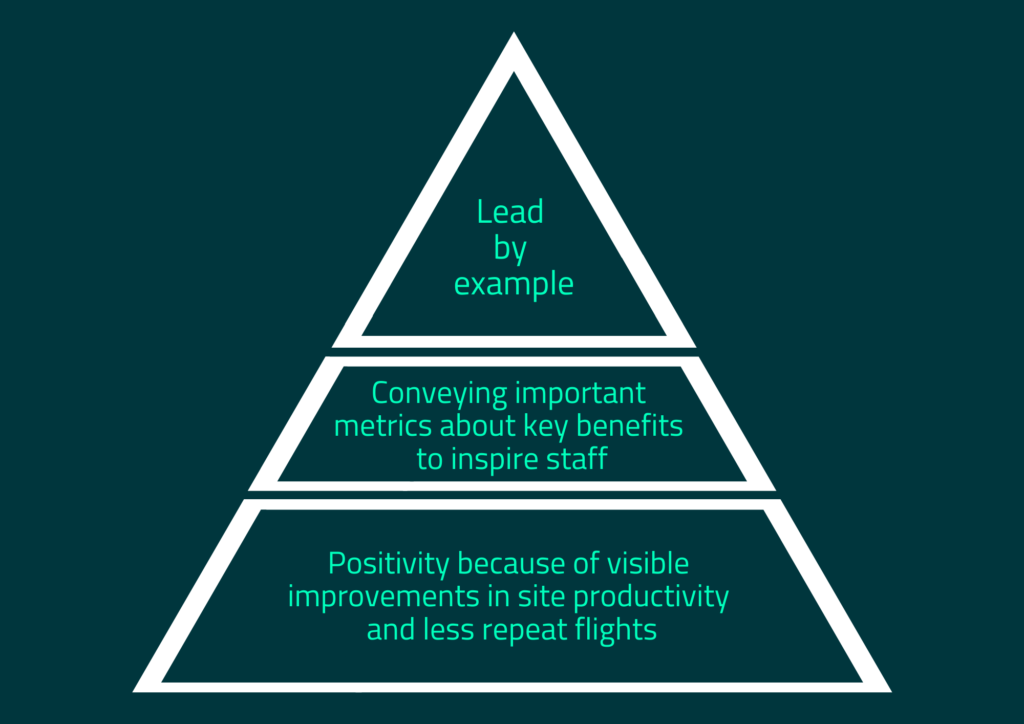

Furthermore, in introducing a new change such as this, the business can expect to face resistance from personnel who have become used to the current arrangements. A culture shift is critical to ensuring the success of a logistical change with clear inconveniences for the employees. Two key methods that can improve this culture of flexibility are to lead by example and to have transparency relating to the benefits leading to this decision.

Leading by example allows management, who will be viewed as responsible for the change, to display that they believe the inconveniences incurred are worth the benefits by being the first to be subjected to these inconveniences on site.

Transparency, especially in exact metrics that matter to the personnel involved, can also encourage those who have to adapt to this change. For example, personnel might be interested to know that the average downtime from maintenance shuts of specific equipment will go down by 2 days due to increased maintenance staff being accommodated on-site at once.

Overall, while operations that use accommodations for their employees cannot offer compensation or monetary incentives as the hospitality industry can, they can focus their strategy on improving the company culture towards accepting change positively.

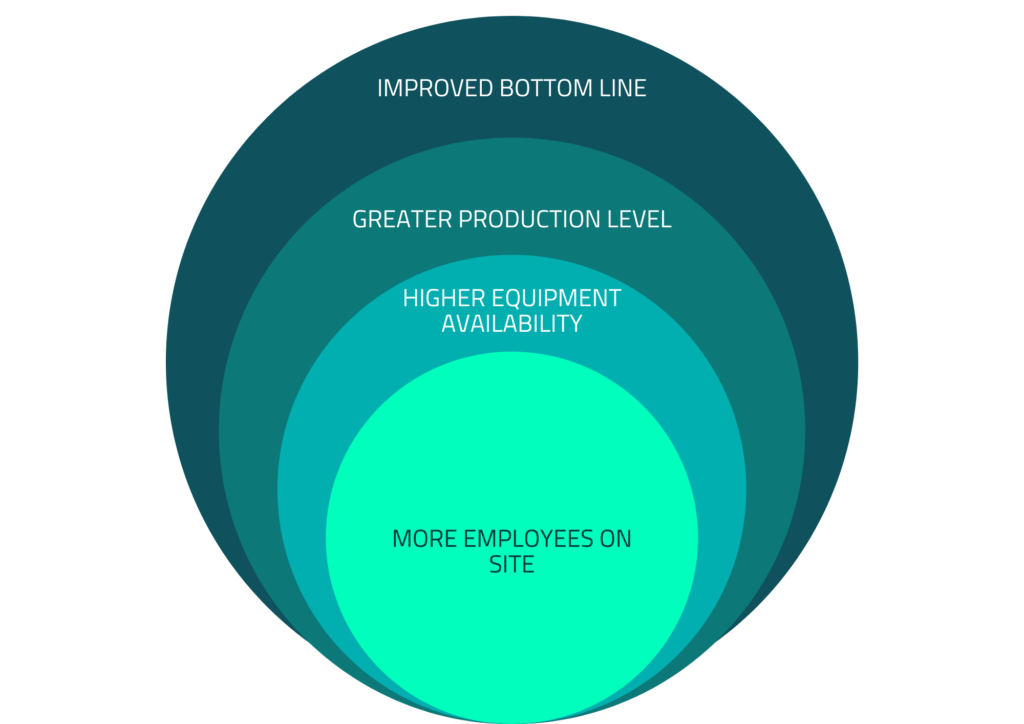

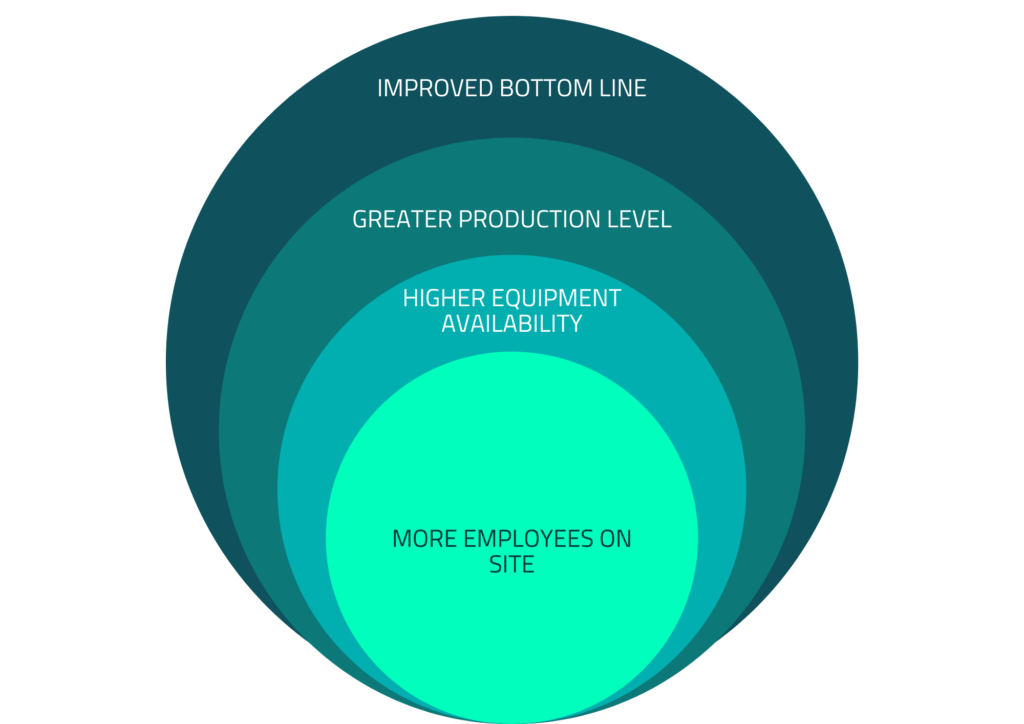

While the challenges are not insignificant, the benefits to this form of operation are also numerous and considerable. For the example of a resource company, more employees can be deployed on-site at any given time due to greater accommodation possibilities. This often leads to greater production efficiencies and hence revenue. Furthermore, the effects are most pronounced during maintenance and shutdown events. Greater accommodation availability results in more maintenance staff being able to be brought in at once, leading to several clear benefits – shorter maintenance and shutdown periods, higher equipment availability, less site downtime, more excellent overall production, and fewer flights required to bring external contractors multiple times for a single maintenance event, amongst others.

In the hospitality scenario, the benefits are obvious – there is minimal increase in operating and running costs with more room availability, but a substantial increase in revenue, as accommodation is the primary service provided. This contributes to an overall improved bottom line.

In order to reliably calculate these benefits, it is essential to have a mathematical model that can handle varying inputs (fixed nights that have already been booked, minimum consecutive nights etc.) to determine basic forecasted improvements and costs.

Visagio has successfully implemented these simulation models, allowing companies to gain visibility into estimated improvements at a quick glance to help decide if split bookings would be useful for a given period. This has allowed for potential savings of up to AU$ 3.6 MM annually within just one division of a company based on reduced maintenance shutdown times by implementing a simple split-booking solution. We have also seen an average of 23% increase in capacity when allowing for split booking shuts with a 3-night minimum consecutive night condition, allowing for cost savings over increasing fixed infrastructure with further site growth.

These simulation models also lead themselves toward full optimisation models that can be customised for additional constraints where required. For example, conditions such as always maintaining a 10% room availability for VIP guests or fixing certain rooms to be fixed and used for full-length bookings. With inputs of all available rooms and current bookings, a full optimiser would best allocate remaining bookings, including determining split durations, to determine maximum utility. The economic problem of limited, scarce resources is well demonstrated in accommodation planning, especially in hospitality businesses and resource industries, amongst others. Moving forward, it is crucial to consider all options to maximise utility rather than simply increasing capacity.

About the author

Anthony Soh is a Management Consultant at Visagio specialising in supply chain management, data analytics, process mapping and logistics optimisation. Anthony holds a Masters Degree in Chemical Engineering and a Bachelor in Science, majoring in Engineering Science and Economics, both from the University of Western Australia.